In the research of the issues that will shape the future of the United States I found the energy and climate change issues were the least understood. This isn’t surprising since significant research and studies on climate change ramped up just 50 years ago. Large advances have been made in our understanding of the dynamics of the world’s ecosystem and the threats of climate change. However, it is an immense, complex task to integrate the results and findings of all the research and studies being done and educate everyone on the latest findings and implications.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)—the intergovernmental body of the United Nations responsible for advancing knowledge on human-induced climate change—was organized to compile the global understanding of human-induced climate change, the natural, political, and economic impacts and risks, and possible response options. The first IPCC “Assessment Report” was published in 1990. In 2015 the IPCC began its sixth assessment cycle and published the initial results of the sixth cycle in 2021. It will complete the sixth cycle in 2023.

A key element of the IPCC assessment process and communication of findings is the application of probabilities and the language of uncertainty to summarize the findings of the thousands of scientific papers available on the various topics at a given time. IPCC reports highlight the ranges of findings and the level of consensus among the hundreds of papers on every topic. Those probabilities and degrees of consensus provide an easy-to-appreciate sense of the research communities’ knowledge of topics and best guesses about the future. While there are criticisms of the reports from all sides, the IPCC organization has done an astonishing job to date capturing the world’s knowledge on climate change every 6 years, showing how that knowledge has changed over the years (since 1990), and presenting the results to the world.

Now that the research and analysis effort is well underway, perhaps the largest challenge the IPCC faces is effective dissemination of the assessment results to update the world on the revised understanding of climate change and its effects. Few outside the scientific community read the reports or the summaries. Most of the world’s population gets their information on the latest IPCC findings from the media. However, the IPCC news is generally lost amongst all the other news about climate change and energy.

This is a significant problem because households, city councils, businesses, and government agencies are making decisions all the time where knowledge and understanding about climate change and energy use are essential. It’s a muddle: No one in the room is ever on the same page, even on the basics. As the knowledge continues to change significantly every six to seven years, this dissemination of results will be a problem.

Everyone needs to learn and believe that IPCC findings should be the basis for decision making. Before a household, city council, business, or government agency decides anything where climate change and energy use are issue, they should ask, “What do we know from the latest IPCC assessment?” Attempting to reason about the implications of climate change and energy use at any level—local, regional, or global—without understanding the latest basic IPCC assessment findings is like driving at night without headlights. IPCC summaries are large, but anyone can learn the basics of what the world “knows” (and doesn’t know), what’s generally predictable in the next thirty years and what’s not.

In the development of the three US scenarios from 2022 to 2050 climate change and energy issues were inseparable. I relied on the IPCC assessment reports, particularly the Sixth Assessment findings released in 2021, the Fifth Assessment cycle reports completed in 2014, and Fourth Assessment cycle reports completed in 2007, on climate change issues. For energy issues, I primarily relied on US Department of Energy projections, International Energy Agency reports, BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2020, and Royal Dutch Shell scenario reports to identify the major drivers.

I divided the combined group of climate change and energy issues into two categories: those with uncertain outcomes over the next thirty years and those with “more predictable” outcomes. This judgment about what can and can’t be predicted in next thirty years is a key factor in any decision about what to do, and when to do it. In the next section I will provide details on the predictable outcomes of the future for climate change and energy that every decision needs to account for. In the section after that, I will lay out possible differences of climate-change and energy outcomes that could emerge from the different dynamics of the three US scenarios.

Predictable Climate-Change and Energy Outcomes, 2022 to 2050

The predictable developments are the foundation and assumptions of the future for the three scenarios.

Understanding of climate change to date. The global understanding of human-induced climate change, the natural, political, and economic impacts and risks, and possible response options continues to advance. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)—the intergovernmental body of the United Nations responsible for advancing knowledge on human-induced climate change—continues to conduct periodic, systematic reviews of all relevant published literature and compile key findings into “Assessment Reports” for policymakers and the public. The scientific community, non-governmental organizations, media, country policymakers, and the public increasingly rely on this “biggest peer review process in the scientific community.”

Atmospheric temperature changes. The IPCC report published in August 2021 had a new important conclusion: the earth is warming. According to the IPCC report global surface temperature was 1.1 °C higher in 2011– 2020 than 1850–1900, with larger increases over land (1.6 °C) than over the ocean (0.9 °C). The report also contained smaller ranges of its global surface temperature projections in the future. By 2050, compared to 1850–1900, global surface temperature is projected to be between 1.6°C and 2.1°C.

Climate-change effects—global: rain, storms, droughts, wildfires, and flooding. According to the latest IPCC reports, because the earth is approximately 1˚C warmer, we are seeing the effects of that warming in the recent temperature extremes, drought conditions and storms around the world. The IPCC report indicates the temperature extremes, drought conditions and storms around the world are likely to get incrementally worse over the next 30 to 80 years.

The average annual global land precipitation is projected to increase by 0–10% by 2081–2100 relative to 1995-2014. Precipitation is projected to increase over high latitudes, the equatorial Pacific and parts of the monsoon regions, but decrease over parts of the subtropics and limited areas in the tropics. The increased atmospheric temperature will lead to an earlier onset of spring snowmelt, with higher peak flows at the expense of summer flows in snow-dominated regions globally.

The warmer climate will intensify very wet and very dry weather and climate events and seasons, with implications for flooding or drought and it is likely that rainfall variability related to the El Niño–Southern Oscillation will be amplified by the second half of the 21st century. Each additional 0.5°C of global warming will cause clearly discernible increases in the intensity and frequency of hot extremes, including heatwaves, heavy precipitation, agricultural and ecological droughts, as well as reductions in Arctic sea-ice, snow cover and permafrost. There will be an increasing occurrence of some extreme events unprecedented in the observational record with additional global warming, even at 1.5°C of global warming.

The IPCC report concluded global mean sea level increased by 0.15 to 0.25 m between 1901 and 2018. By 2050, the increase in global mean sea level will be 0.30 to 0.45 m higher than it was in 1901.

Climate-change effects, United States: rain, storms and flooding, droughts, and wildfires. The western, central, and eastern regions of the United States will experience higher warming levels like the rest of the globe. Central and western United States will have increases in drought and fire weather.

The 2021 IPCC report said, “. . . as global temperatures rise . . . [in the United States] precipitation and surface water flows [are] projected to become more variable over most land regions within seasons, and from year to year.”

The average amount of precipitation per year in all three regions of the United States—western, central, and eastern—will remain at least the same, even in the western part. There’s a good chance the eastern part of the United States will see higher averages; there is some chance the western and central regions will have higher averages.

There will be, in the words of the IPCC, “clearly discernible increases in the intensity and frequency of hot extremes, including heatwaves, heavy precipitation, agricultural and ecological droughts, as well as reductions in Arctic sea-ice, snow cover and permafrost [in and around Alaska].”

Technology to limit GHGs emissions or remove GHGs from atmosphere. Large scale projects in afforestation (planting trees) and direct carbon capture systems won’t have a significant impact on greenhouse gas levels in the atmosphere before 2050 because the technologies can’t be commercialized and implemented in time. It’s uncertain, but plausible that some technologies could have a large impact on GHGs in the atmosphere from in the period from 2050 to 2100.

Energy consumption in emerging economies. Emerging economies, including China and India, accounted for approximately 60 percent of the world’s energy consumption in 2020. This will increase to approximately 70 percent in 2050.

World energy intensity. The GDP growth of non-OECD countries from 2020 to 2050 will drive down global energy intensity by 40 to 50 percent. Energy intensity is the measure of how much energy is required for each unit of GDP. In 2015, energy intensity was 4.5 MJ per US$ of GDP. In a market economy, competitive pressures result in energy efficiencies, lower energy costs, and lower energy intensity. When the global economy is growing, energy intensity drops approximately 2 percent per year.

China’s installed hydrocarbon capacity to generate electricity. Installed hydrocarbon capacity used to general electricity (mix of natural gas and coal) will grow from 4600 gigawatts capacity in 2019 to about 5200 GW in 2050.

Summaries of the three US 2050 Scenarios

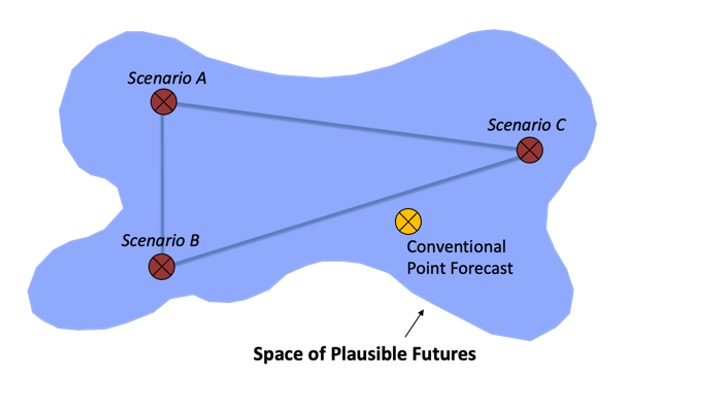

The three scenarios of the United States’ future from 2022 to 2050 were created to explore possible outcomes and interactions of four overarching uncertainties: (1) the role of the US government in society, (2) the strength of the US economy, (3) China’s strategy in the struggle against the U.S. to shape world order, and (4) global energy use and greenhouse-gas (GHG) emissions.

Socially Divided. The development that defines Socially Divided is China’s brutal nationalism and displacement of the United States as the world’s number one superpower. China asserts its regional dominance of Asia, and attacks and overwhelms Taiwan. U.S. society is deeply divided and control of the US federal government bounces between Democrats and Republicans. U.S. government programs are added to focus on domestic social and energy/climate problems and U.S. federal government spending expands from 21% of GDP in 2019 to 30% in 2050. Global economic growth is modest from 2021 to 2050; rates for the U.S. and China are 1.3 percent/yr and 3.1 percent/yr, respectively. The world, led by China and India, develops extensive new renewable energy supplies to maintain strong global economic growth but continues to rely on large volumes of hydrocarbons through 2050. Total GHG emissions slowly decline from 55 GtCO2e/yr in 2020 to 45 GtCO2e/yr in 2050.

Security United: The signature event of the “Security United” scenario is the global depression from 2026 to 2035 brought on by China’s collapsing economy. US economic growth is weak—U.S. GDP growth averages 1.1 percent per year from 2021 to 2050—but the best in a global depression. China’s grow in the same period is 0.4 percent per year. As the world economy entered the depression, the US government focused on economic and geopolitical security issues without expanding the size of government. U.S. federal government spending still increases from 21% of GDP in 2019 to 24% in 2050. With the onset of the depression, China stepped back plans to forcefully assert sovereignty over Taiwan. The only “good” news of Security United is the world comes close to achieving its goal of “net-zero” emissions of CO2 by 2050 (from 40 GtCO2 in 2020) by slowing the demand for energy and using less hydrocarbons in energy supply.

Economy Focused: China and the U.S. remain neck and neck in the global competition for economic power from 2022 to 2050. China is passive aggressive toward the U.S., playing the long game to become the world’s economic superpower. China seeks to overwhelm Taiwan peacefully. The U.S. government focuses on security and economic issues without expanding the role and size of the U.S. government. U.S. federal government spending still increases from 21% of GDP in 2019 to 25% in 2050. U.S. GDP growth averages 2.0 percent per year from 2021 to 2050. After the Glasgow Climate Change meeting in 2021 and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the advanced economies accomplish an “about-face” on eliminating the use of natural gas and oil and limiting the use of nuclear energy. Greenhouse gas emissions remain high through 2050 but are beginning to decline rapidly because of advances and implementation of carbon capture and storage systems at the end of the scenario. By 2050 China’s economy is twice as large as the U.S. economy, and India’s economy is substantially larger than the U.S.’s.

Socially Divided Scenario: Climate-change and Energy Outcomes, 2022 to 2050

Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from 2021 to 2050, GtCO2e/yr. Total GHG emissions decline from 55 GtCO2e/yr in 2020 to 45 GtCO2e/yr in 2050. For CO2—the largest GHG—emissions decline from 40 GtCO2/yr in 2020 to 25 GtCO2/yr in 2050.

Atmospheric concentration levels of CO2, ppm (parts per million). Atmospheric concentration of CO2 rises from approximately 400 ppm in 2020 to 475 ppm in 2050. (It is projected to reach 550 ppm in 2100 and level off at 600 ppm in 2300.)

International policy efforts related to energy use and climate change. Advanced economies (led by the US and EU) and emerging economies (led by China and India) implement different strategies to fight climate change. Advanced economies strive to reduce the use of hydrocarbons as quickly as possible (net zero CO2 emissions by 2050) and scale up renewable energy sources as rapidly as possible; while emerging economies want to continue growing their economies, leveraging hydrocarbons for energy until renewable energy sources are plentiful enough and cheap enough to replace the hydrocarbons.

Advanced economies implement carbon pricing systems and new regulations designed to accelerate the transition away from hydrocarbons. The advanced economies also subsidize significant investments in renewable energy technologies to generate the electricity.

The US and EU agree on a system of carbon tariffs and financial subsidies to emerging economies for green power generation projects.The BRIICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, Indonesia, China, and South Africa), South Korea and Japan vehemently protest any carbon-sanction policy by the US and EU.

China and India stop providing data on their energy use, GHG emissions, country climate conditions.

Despite the many problems, emerging economies led by China succeed in making large investments in wind, solar, and nuclear.

Government budgets for large-scale climate-change adaptation and mitigation measures worldwide. Advanced economies invest in initiatives to eliminate hydrocarbons as a source of energy, accelerate the development of renewable energy sources, and develop afforestation to pull CO2 from the atmosphere.

Government funding for mitigation projects in advanced economies quickly ramps up to on average 2 percent of GDP per year. In the United States this spending is around $400 billion/year.

Emerging economies focus their climate-change mitigation investments on building renewable energy sources. China’s average spending on climate-change mitigation is 1 percent of GDP/yr, most of it focused on the development of renewable energy, battery, nuclear energy, and carbon capture systems. In most emerging economies government spending on mitigation projects (mostly the electrification of their economies) is less than 0.25 percent of GDP/yr.

Large scale projects in afforestation (planting trees) result in a total of 5 GtCO2 in 2050 compared to zero GtCO2 being captured in 2020. Large-scale direct carbon capture systems aren’t implemented before 2050.

China government policies implemented to mitigate and adapt to climate change. China continues to rely on hydrocarbons for economic growth and refuses to limit their use.

In the early 2020s China accuses the United States of attempting to sabotage China’s, India’s, and African economic growth prospects by its promotion of global sanctions to limit the use of oil and coal.

China makes heavy investments in nuclear energy, solar and wind energy, and battery technology and develops monopolistic positions in many critical materials required for clean energy.

US federal policies enacted: Energy and climate change. The US implements new policies and regulations to mitigate climate change by eliminating US greenhouse gas emissions. The effort is two-pronged: 1) eliminate the use of hydrocarbons in the economy and 2) stimulate development of renewable energy sources and electrification of the economy.

Emergency spending measures are required almost every year at the federal level to assist the nation in dealing with extreme weather events: floods, droughts, wildfires, freezes. State emergency response agencies are often overwhelmed.

Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates United States spending on mitigation is around 2 percent of GDP ($400 billion/year) and adaptation spending in the US averages about 1 percent of GDP per year ($200 billion).

The US and EU agree on a system of carbon tariffs, despite vehement objections by China, India, and the rest of the emerging economies. The US and EU also agree on a system of financial subsidies to emerging economies for green power generation projects.

World energy consumption, EJ/yr. World energy consumption increases to 725 EJ/yr in 2050 from 570 EJ/yr in 2020.

| Year 2020 | Year 2050 | |

| Oil | 172 | 130 |

| Natural Gas | 135 | 170 |

| Coal | 151 | 100 |

| Nuclear | 29 | 50 |

| Hydro | 18 | 40 |

| Bio | 56 | 60 |

| Solar and Wind | 9 | 175 |

| Total | 570 | 725 |

| Developed Economies | 235 | 210 |

| US | 95 | 80 |

| EU | 70 | 60 |

| Emerging Economies | 335 | 515 |

| China | 140 | 155 |

| India | 36 | 80 |

Advanced economies led by the US continue to implement policies to dramatically reduce their use of hydrocarbons by 2050 and meet future energy requirements largely with wind and solar.

The electrification of power generation worldwide is enabled by enormous investments in China and India in nuclear energy, solar and wind energy, and battery technology. However, the electrification of the world’s economy is expensive, and not smooth. Power outages are frequent.

Hydrocarbon energy costs fluctuate wildly from year to year, and China, India and South Africa have significant energy-security problems. China and India reject calls to slow their economies by reducing their use of hydrocarbons.

Average household energy bills in emerging market and developing economies increase by 50 percent in real terms from 2021 to 2050; in advanced economies average household bills stay level in real terms from 2021 to 2050.

Energy required to generate electricity. The percentage of final energy used to generate electricity around the world rises from 20 percent in 2019 to 40 percent in 2050.

Wind and solar generation capacity, GW. Wind and solar-electricity generation capacity increases from 880 GW in 2019 to 16,000 GW in 2050.

Coal consumption in world (EJ/yr). Coal consumption around the world declines only from 151 EJ/yr in 2020 to 100 EJ/yr in 2050, representing 14 percent of total world final energy consumption.

Passenger vehicle energy consumption (hydrocarbons v. electricity). Cars and small trucks’ consumption of energy declines from 56 EJ/yr (53 EJ/yr gasoline, 1 EJ/yr electric) in 2019 to 49 EJ/yr (28 EJ/yr gasoline, 20 EJ/yr electric) in 2050.

Security United Scenario: Climate-change and Energy Outcomes, 2022 to 2050

Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from 2021 to 2050, GtCO2e/yr. Total GHG emissions decline from 55 GtCO2e/yr in 2020 to 20 GtCO2e/yr in 2050. For CO2—the largest GHG—emissions decline from 40 GtCO2/yr in 2020 to 5 GtCO2/yr in 2050.

Atmospheric concentration levels of CO2, ppm (parts per million). Atmospheric concentration of CO2 rises from approximately 400 ppm in 2020 to 450 ppm in 2050. (It is projected to reach 500 ppm in 2100 and fall to 400 ppm in 2300.)

International policy efforts related to energy use and climate change. Advanced economies attempt to regulate out use of hydrocarbons in their economies and invest heavily in renewable energy technologies to generate the electricity to replace the hydrocarbon fuels. Many countries implement forms of carbon taxes, carbon tariffs, and green offsets to shape the behavior and investments of businesses and consumers and government policies around the world.

Emerging economies struggle with energy security and resist efforts by the advanced economies to limit their use of hydrocarbons. China, India, and South Africa, refuse to limit the use of coal or natural gas in electricity generation and protest the carbon tariffs. China and India stop providing data on their energy use, GHG emissions, country climate conditions.

UN climate conferences become contentious affairs between emerging and advanced economies. Few countries meet their commitments.

After the global depression hits in 2026, governments generally abandon carbon taxes and hydrocarbon restrictions. GHG gas emissions are going down “fast enough” due to the depression.

Government budgets for large-scale climate-change adaptation and mitigation measures worldwide. Government investment focus worldwide is on mitigation—eliminating hydrocarbons as a source of energy and accelerating the development of renewable energy sources.

Spending by governments in advanced economies on mitigation projects vary from 0.5 percent of GDP/yr to 1.5 percent of GDP/yr.

The emerging economies generally ignore efforts by the advanced economies to reduce the emerging economies’ use of hydrocarbons.

In the advanced economies and China and India, energy costs increase significantly because of expensive investments to electrify their economies. As a rule, the investment costs are much higher than expected while the mitigation benefits (lower energy prices) rarely materialize. Renewable energy capacity climbs slowly and hydrocarbons remain a key element of each country’s energy security.

Large-scale projects to pull CO2 from the atmosphere, by either planting millions of trees or capturing the CO2 emissions in using hydrocarbons for energy, aren’t implemented because of their infeasibility.

Despite the focus on mitigation, adaptation spending increases around the world on emergency response for extreme climate events and new civil infrastructure. It’s hard to quantify but adaptation spending averages about 1 percent of GDP per year in advanced economies and China, and 0.5 percent of GDP per year in emerging economies.

China government policies implemented to mitigate and adapt to climate change. China continues to invest heavily in renewable energy industries and electric cars.

However, it doesn’t try to curtail its use of hydrocarbons in the economy and accuses the United States of attempting to sabotage its economy and insisted the United States stop meddling in the energy strategies of emerging economies.

China declares the United States is using its military presence in the South China Sea to limit the development and flow of oil, gas, and coal resources throughout Asia and must leave.

As the world depression unfolds beginning in 2025, China’s GHG emissions decline rapidly.

US federal policies enacted: Energy and climate change. Federal government policy is largely focused on mitigation, i.e., eliminating hydrocarbons as a source of energy and accelerating the development of renewable energy sources.

The US and EU push for an international system of carbon tariffs on trade but they fail because of fierce objections by the developing economies, particularly China and India.

CBO estimates federal spending on mitigation at 1.25 percent per year ($250 billion/yr).

After the global depression hits in 2026, the US reverses its efforts to limit natural gas usage. It is now an important transition fuel.

Despite the focus on mitigation, US spending on emergency responses to extreme climate events and new civil infrastructure increases. US spending is estimated at about 1 percent of GDP per year. However, the states and federal government struggle to coordinate their emergency responses and political crises topple many elected officials.

World energy consumption, EJ/yr. World energy consumption decreases to 480 EJ/yr in 2050 from 570 EJ/yr in 2020.

| Year 2020 | Year 2050 | |

| Oil | 172 | 100 |

| Natural Gas | 135 | 100 |

| Coal | 151 | 80 |

| Nuclear | 29 | 40 |

| Hydro | 18 | 30 |

| Bio | 56 | 40 |

| Solar and Wind | 9 | 90 |

| Total | 570 | 480 |

| Developed Economies | 235 | 170 |

| US | 95 | 70 |

| EU | 70 | 55 |

| Emerging Economies | 335 | 310 |

| China | 140 | 120 |

| India | 36 | 70 |

In the 2020s many advanced economies implemented policies to limit future use of coal, natural gas and oil. However, renewable-energy generation and transmission-line capacity failed to materialize quickly, and the advanced economies continue to rely on hydrocarbons. Power outages are a frequent occurrence in many countries beginning in the mid-2020s.

The world energy situation dramatically improves when the global economy turns negative in 2026 and demand for hydrocarbon falls.

Prices for oil, natural gas, and coal remain volatile, even during the depression, and energy-security issues challenge country leaders.

Average household energy bills in emerging market and developing economies double in real terms from 2021 to 2025 and remain there on average through to 2050; in advanced economies average household bills increase 25 percent in real terms from 2021 to 2025 and then decrease by a third in real terms from 2026 to 2050.

Consumer and business protests over energy bills are extreme everywhere. Many governments reverse their policies toward hydrocarbons.

Energy required to generate electricity. The percentage of final energy used to generate electricity around the world rises from 20 percent in 2019 to 40 percent in 2050.

Wind and solar generation capacity, GW. Wind and solar-electricity generation capacity increases from 880 GW in 2019 to 8,000 GW in 2050.

Coal consumption in world (EJ/yr). Coal consumption around the world declines significantly from 151 EJ/yr in 2020 to 80 EJ/yr in 2050, representing 17 percent of total world final energy consumption.

Passenger vehicle energy consumption (hydrocarbons v. electricity). Passenger vehicles consumption of energy declines from 56 EJ/yr (53 EJ/yr gasoline, 1 EJ/yr electric) in 2019 to 45 EJ/yr (35 EJ/yr gasoline, 10 EJ/yr electric) in 2050.

Economy Focused Scenario: Climate-change and Energy Outcomes, 2022 to 2050

Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from 2021 to 2050, GtCO2e/yr. Total GHG emissions rise from 55 GtCO2e/yr in 2020 to 60 GtCO2e/yr in 2030 before falling back to 55 GtCO2e/yr in 2050. CO2 emissions decline from 40 GtCO2/yr in 2020 to 39 GtCO2/yr in 2050.

Atmospheric concentration levels of CO2, ppm (parts per million). Atmospheric concentration of CO2 rises from approximately 400 ppm in 2020 to 500 ppm in 2050. (It is projected to level off at 600 ppm in 2100 and remain at that level until 2300.)

International policy efforts related to energy use and climate change. Working through UN climate conferences, countries pursue individual national strategies for energy security, protecting themselves from the effects of climate change, reducing GHG emissions, making their countries more economically and physically resilient. For most, the priorities to 2050 are to diversify energy sources (but not to eliminate hydrocarbon usage) and protect themselves (modify civil and social infrastructure) for the anticipated effects of climate-change in the next thirty years and beyond.

China and India discourage but don’t limit the use of coal. Heavy investments are made in large-scale wind, solar, and new nuclear systems to meet energy demand needs and improve energy efficiencies, and in large-scale carbon-capture systems.

Many countries successfully implement forms of carbon taxes to shape the behavior and investments of businesses and consumers.

Government budgets for large-scale climate-change adaptation and mitigation measures worldwide. Government climate-change investments are focused on ameliorating the climate-change effects already being experienced. They include increased emergency response spending for extreme climate events and capital for new civil infrastructure for the changing environment. It’s hard to quantify but adaptation spending averages about 1.5 percent of GDP per year in advanced economies and China, and 1.0 percent of GDP per year in emerging economies.

Government monies for mitigation are limited to R&D in renewable energy, next generation of nuclear energy technologies, and large-scale carbon capture systems. In advanced economies, China and India, total government mitigation investments are on the order of 0.25 percent of GDP/yr. In the US, they are 0.5 percent per year.

Large scale efforts in afforestation (planting trees) don’t take off, but direct carbon capture systems are commercialized in the early 2040s. The result is by 2050 4 GtCO2/yr being are being removed and this amount is increasing rapidly.

The crises from droughts, floods, wildfires, and food supply issues are getting worse but the world is adapting to the changed environmental conditions.

China government policies implemented to mitigate and adapt to climate change. China pushes back against foreign efforts to curtail China’s use of hydrocarbons.

China’s climate-change investments are largely aimed at mitigating the effects of natural disasters caused by the increased atmospheric temperatures and building market-leading positions in solar renewable energy systems, electric vehicles, batteries, and nuclear power generation.

US federal policies enacted: Energy and climate change. Supported by both the Republicans and Democrats, the US energy/climate change policy is to encourage diversity of energy supply, accept long-term use of natural gas as a transition fuel, re-energize nuclear power, and, of course, expedite approvals of new renewable-energy installations. While private investments flow into increasing US electricity generation capacity, government monies focus on reducing the effects of heat waves, droughts, river flooding, and wildfires. In the western United States, federal government and state governments overhaul land-use and water-rights laws and regulations.

The US implements a carbon tax in the US to shape the behavior and investments of businesses and consumers. A global system for carbon tariffs is also implemented after the EU, China, India, and US agree to support a system and the WTO adjusts its rules to enable carbon tariffs in trade agreements.

Federal government investments are focused on ameliorating the climate-change effects already being experienced. They include increased emergency response spending for extreme climate events and capital for new civil infrastructure for the changing environment. It’s hard to quantify but adaptation spending averages about 1.5 percent of GDP per year.

Government monies for mitigation are limited to R&D in renewable energy, next generation of nuclear energy technologies, and large-scale carbon capture systems. In the US, spending on mitigation is 0.5 percent of GDP per year.

World energy consumption, EJ/yr. World energy consumption increases to 845 EJ/yr in 2050 from 570 EJ/yr in 2020.

| Year 2020 | Year 2050 | |

| Oil | 172 | 150 |

| Natural Gas | 135 | 170 |

| Coal | 151 | 80 |

| Nuclear | 29 | 115 |

| Hydro | 18 | 60 |

| Bio | 56 | 90 |

| Solar and Wind | 9 | 180 |

| Total | 570 | 845 |

| Developed Economies | 235 | 210 |

| US | 95 | 100 |

| EU | 70 | 60 |

| Emerging Economies | 335 | 635 |

| China | 140 | 155 |

| India | 36 | 90 |

Following the Glasgow Climate Change meeting in 2021, the advanced economies accomplish an “about-face” on eliminating the use of natural gas, oil and nuclear. Natural gas and oil are viewed as critical to a successful transition of the world’s economy to electrification by the end of the century. Their policy priorities are: nuclear and hydrogen energy generation, renewable energy. energy-storage systems, technologies to adapt society to climate-change effects, and technology development of carbon-capture systems.

The use of hydrocarbons finances the transition to clean energy sources. Carbon taxes and tariffs are slowly but steadily increased.

Average household energy bills in emerging market and developing economies increase by 75 percent in real terms from 2021 to 2025; in advanced economies average household bills decline by 30 percent in real terms from 2021 to 2050.

Energy required to generate electricity. The percentage of final energy used to generate electricity around the world rises from 20 percent in 2019 to 34 percent in 2050.

Wind and solar generation capacity, GW. Wind and solar-electricity generation capacity increases from 880 GW in 2019 to 12,000 GW in 2050.

Coal consumption in world (EJ/yr). Coal consumption around the world declines from 151 EJ/yr in 2020 to 80 EJ/yr in 2050, representing 9 percent of total world final energy consumption.

Passenger vehicle energy consumption (hydrocarbons v. electricity). Passenger vehicles consumption of energy increases from 56 EJ/yr (53 EJ/yr gasoline, 1 EJ/yr electric) in 2019 to 92 EJ/yr (72 EJ/yr gasoline, 16 EJ/yr electric) in 2050.